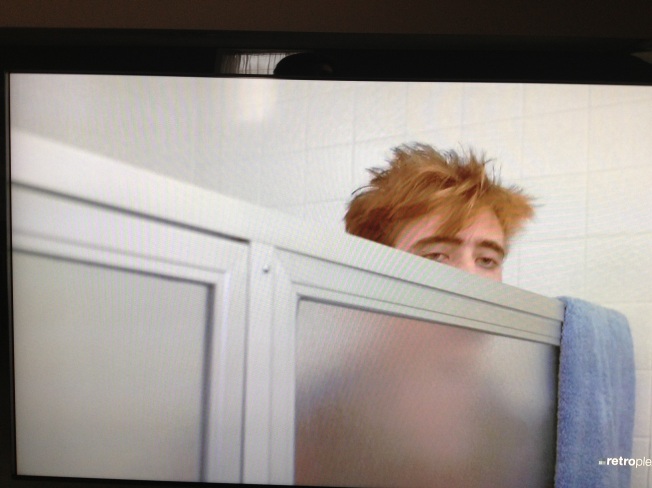

“Let’s get out of here.” Randy (Nicolas Cage) waits to meet Julie (Deborah Foreman) in the bathroom at Suzi’s party in the Valley.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Visions of Light (1992)

Visions of Light is a documentary about the history of cinematography. I didn’t know what cinematography was until I took a film class at Florida State University (which has a darned good film school, by the way). My instructor, with her German accent (it seemed so fitting for a film class), explained cinematography simply as “what you see in the frame.” Visions traces the evolution of cinematography through the limitations – and resulting creativity – of the technology, including the earliest cameras, the arrival of sound (and the havoc it wreaked when noisy cameras had to be contained in soundproof booths, thereby greatly limiting the cinematographer’s freedom to move the camera), the introduction of color (also seen as a hindrance in some ways), and the invention of CinemaScope and Panavision – broadening the screen from a square to a wide rectangle and giving cinematographers more space to shoot. Cinematographers between the 1950s and 70s also had to consider how the film would look projected at drive-in theaters (which tended to wash out color and the nuances of anything less than bright lighting).

The “eyes of the cinematographer” is another concept explored. Nestor Almendros (cinematographer for Days of Heaven, 1978; Kramer vs. Kramer, 1979; and Sophie’s Choice, 1982) shares his insight on the frequency in which a foreigner is chosen for cinematographer – “The cinematographer is often from another country…A foreigner has a fresh eye to look…maybe he sees better, what is interesting.”

This engrossing documentary offers up insider information like why Brando’s eyes were shot in shadow for The Godfather (and how the studio fought the “lack of lighting” in the film), how a cinematographer’s livelihood depended on how beautiful he made the stars look on film, and how filming “mistakes” (such as the sun flashing off the camera’s lens) became hallmark techniques of some DPs in the experimental 1970s.

Light, shadows, color, lack of color, positive and negative space – the cinematographer’s realm is full of contrasts. In discussing the use of darkness in film noir, another DP observes, “Film noir is not afraid of the dark. In noir, black is not negative space. It’s often the most important element of the scene.” Ernest Dickerson (cinematographer for Do the Right Thing, 1989) says, “The director is the author of the performances…of the story. The cinematographer is the author of the use of light in the film and how that contributes to the story.”

Visions offers up a terrific sampling of clips from classic cinematographic shots. Citizen Kane, The Killers, On the Waterfront, The Godfather, and Chinatown are portrayed — as would be expected. But the film offers a broad range of cinematic examples: The Magnificent Ambersons (1942, Joseph Cotten); What Price Hollywood? (1932, Constance Bennett); Possessed (1947, Joan Crawford); Queen Christina (1933, Greta Garbo); Sweet Smell of Success (1957, Tony Curtis); The Conformist (1970, Jean-Louis Trintignant); In Cold Blood (1967, Robert Blake); Young Man With a Horn (1950, Kirk Douglas); The Naked City (1948, Barry Fitzgerald) and Days of Heaven (1978, Richard Gere) all made my list to see (or see again). My interest was piqued by the commentary on all these clips and yet the visual impact of just a few seconds of each was enough to make me want to seek them out. That, I think, is cinematography.

Here’s the Siskel & Ebert TV show review of Visions of Light with some good clips from the film:

Welcome to Moviequail

Moviequail is a blog of minimalist proportions. Title, format viewed (big screen, disc, streaming, TV), notable talent (actors, directors, screenwriters), preconceived notions and after-viewing impressions will all be addressed in a concise format. I hope you find it useful when choosing a movie or deciding whether to see something again.